Cattle, greenhouse gases and the case for better methane metrics

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

The first Global Methane Status Report, released at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, shows meaningful progress toward cutting global methane, along with a clear need for further action.

Produced by the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC), the report projects an 8% methane reduction by 2030 under today’s commitments. This progress is worth noting, but achieving the pledge’s goal of a 30% reduction (from 2020 levels) will require the rapid scaling of policies, technologies and partnerships across energy, agriculture and waste industries. And with enteric methane from cattle and other ruminants accounting for roughly one third of human-caused methane emissions, cows are central to the conversation.

But what if the challenge isn’t only methane itself, but the way we’ve been measuring it?

Each greenhouse gas (GHG) has a global warming potential (GWP) value that measures its ability to trap heat in the atmosphere. GWP is an indicator of how potent GHG emissions are and of the role they play in warming the planet.

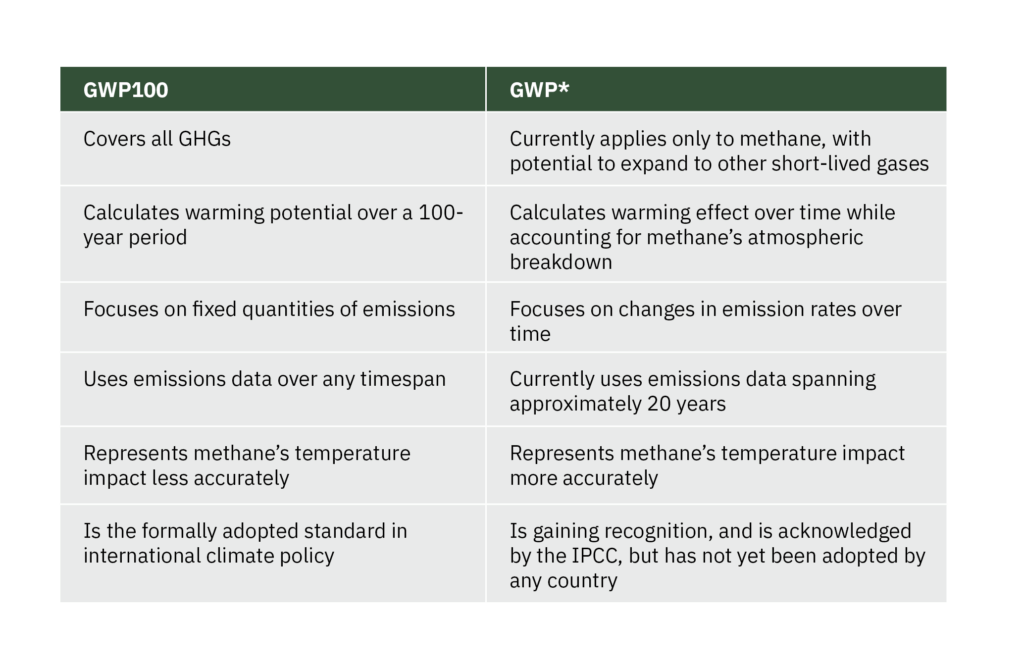

Since 1990, the standard metric used to measure GHG emissions, including methane, has been GWP100, which expresses the heat-trapping ability of a specific gas over a 100-year time span. But this metric doesn’t account for the fact that methane is a flow gas, not a stock gas like carbon dioxide.

Imagine two bathtubs filling up with water. In one tub, the faucet runs and there’s no drain. With every second, the water level rises. The other tub, though, has an open drain. The water’s still pouring in, but it’s also constantly draining out. If the flow from the faucet stays steady, the water level in this second tub settles instead of climbing.

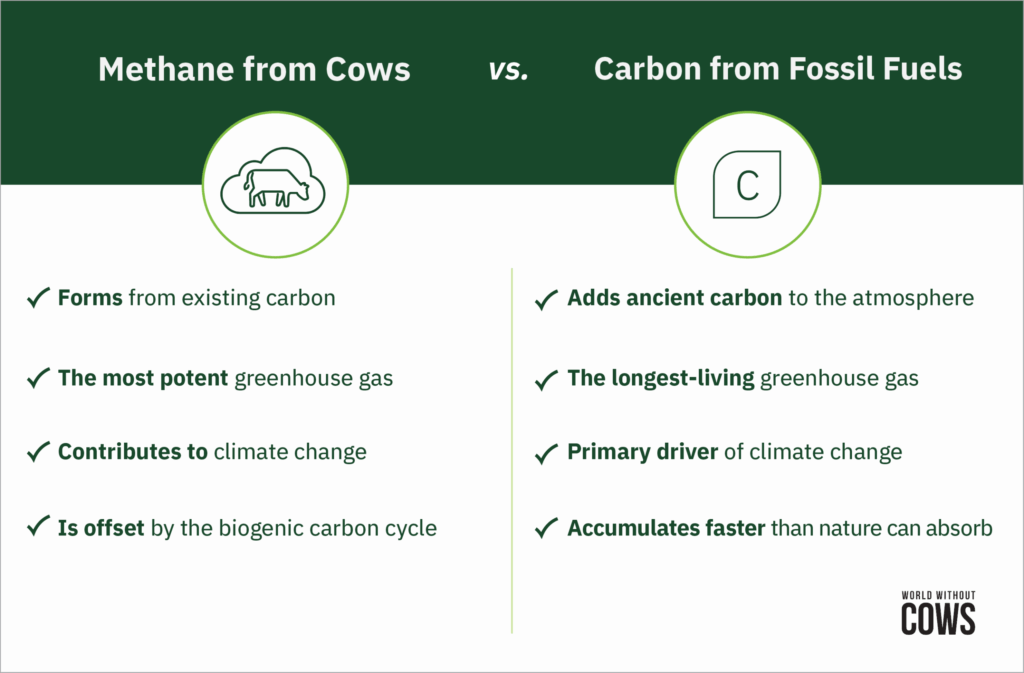

Carbon dioxide generated from fossil fuels is a stock gas, meaning it behaves like the water in the drainless tub. It accumulates in the atmosphere for thousands of years, where it continuously adds to global warming. Methane, on the other hand, is a flow gas that breaks down in the atmosphere within about 10 to 12 years when the gas reacts with hydroxyl radicals to and water vapor.

Keep in mind that CO₂ from methane isn’t the same as CO₂ from fossil fuels because it’s biogenic, which means it’s produced within a natural plant-animal cycle rather than added as new carbon from long-stored fossil reserves. So instead of continuously rising like the water in the drainless tub, methane levels plateau — and, in some cases, even decline.

Using a single metric to measure two gases that behave very differently in the atmosphere makes an already complex system more difficult to navigate. By failing to account for methane’s much shorter lifespan and its tendency to plateau or decline when emissions stabilize, cattle production appears to accumulate a “carbon debt” over time, even if producers are effectively slowing down their warming contributions. Essentially, by treating methane as if it persists for a century, it can look like cows are adding more warming year after year, even though methane breaks down at a much faster rate and may no longer be contributing heat to the atmosphere.

The scientific solution to this measurement gap is the Global Warming Potential Star (GWP*), a metric created to more precisely account for the unique warming impact of short-lived gases like methane. Developed by a team of researchers led by Professor Myles Allen of the University of Oxford, and first named in a study in 2018, GWP* measures the warming impact of methane by averaging its effect over a period of about 20 years, rather than 100 years like GWP100 does. This approach models the change in emission rates over time, recognizing that when emissions remain constant, the warming effect is relatively negligible because the rate of older methane breaking down balances out the warming of new methane additions.

When researchers at the Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3) applied this metric to historical data, they found that since 1981, the cumulative warming-equivalent emissions from cattle methane are 28–44% lower when measured with GWP* compared to GWP100. This gap matters, because it shapes how the world understands the environmental footprint of cows and builds policies around it.

Although GWP* offers a more advanced way to describe methane’s temperature impact under changing emissions, GWP100 remains the primary metric because it is the formally adopted standard under the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reporting guidelines. More than three decades of policy integration have created significant institutional momentum that makes rapid shifts challenging.

Because GWP100 is the global standard, adopting a new metric such as GWP* would require coordinated changes across countries, industries and data systems. And, while GWP* captures methane’s warming potential more precisely under changing emissions, some researchers and climate groups worry that it could be misused by high-emitting sectors and regions to appear climate-neutral with only minor reductions.

Globally, conversations about methane accounting are becoming more urgent, especially in regions where beef and dairy cattle production is increasing to keep up with demand for meat and milk. For example, projections show that Asia will see the largest absolute increase in terrestrial animal-sourced foods by 2050. With this expansion, the region is at the forefront of the need for precise methane measurement and mitigation strategies for producers. In India specifically, more than 300 million cattle and buffalo produce 14% of global livestock emissions. For a nation with the world’s largest cattle population, using GWP* could potentially offer a more accurate baseline for identifying priorities and directing climate investments.

Other agricultural regions are exploring what the shift to this metric could mean for farming emissions. New Zealand, for example, has been evaluating how GWP* can guide biogenic methane targets in a way that aligns with real temperature impacts.

The global cattle industry and methane are at the center of conversations about food security, nutrition and climate. The challenges producers face are real, and no one benefits from pretending otherwise. But by acknowledging the complexity and focusing on solutions, we can identify a better way forward.

Adopting GWP* will not make methane go away, nor does it minimize the significance and urgency of reducing emissions from cattle. What it can do is improve our ability to set realistic targets, verify outcomes and develop solutions that reflect real temperature impacts.

These nuances are explored further in World Without Cows, a feature-length documentary that examines the cultural and economic significance of cattle, their role in nourishing the world and their impact on the climate.

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

At COP30, the world’s eyes are on Brazil, and the cattle ranchers leading a global transformation.

Restoring 40 million hectares of pasture could feed billions and ease pressure on the Amazon. Is the world paying attention?

New mini-doc explores deforestation, food security and the Brazilian cattle sector’s path to a more sustainable future

Mention Brazilian beef, and you’re likely to spark discussion about familiar themes: deforestation, emissions and blame. What do we find when we dig deeper? Here are the answers to five top questions about Brazil’s role in protecting the Amazon and feeding the world.

From science to the big screen: Discover how a single question grew into a global journey.

As climate change intensifies and the world’s population continues to grow, the pressure on our global food production system mounts. You can play an active role in shaping a more sustainable planet for future generations. Fill out the form below to learn more about how you can partner with us.

Receive notifications about the release date, new online content and how you can get involved