Cattle, greenhouse gases and the case for better methane metrics

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

On Gabe Brown’s 5,000-acre ranch in Bismarck, North Dakota, the pastures don’t sit idle. They’re alive with movement: cows grazing their way from paddock to paddock, grass bouncing back and soil rebuilding itself beneath the surface.

That’s because Gabe, a fifth-generation farmer, doesn’t treat his land as just a tool for production — he sees it as a living, breathing system.

Over two decades ago, after back-to-back weather disasters nearly broke his operation, Gabe made a bold decision. He abandoned synthetic fertilizers, embraced cover crops, and adopted a grazing method inspired by nature: small paddocks, short grazing intervals, long rest periods.

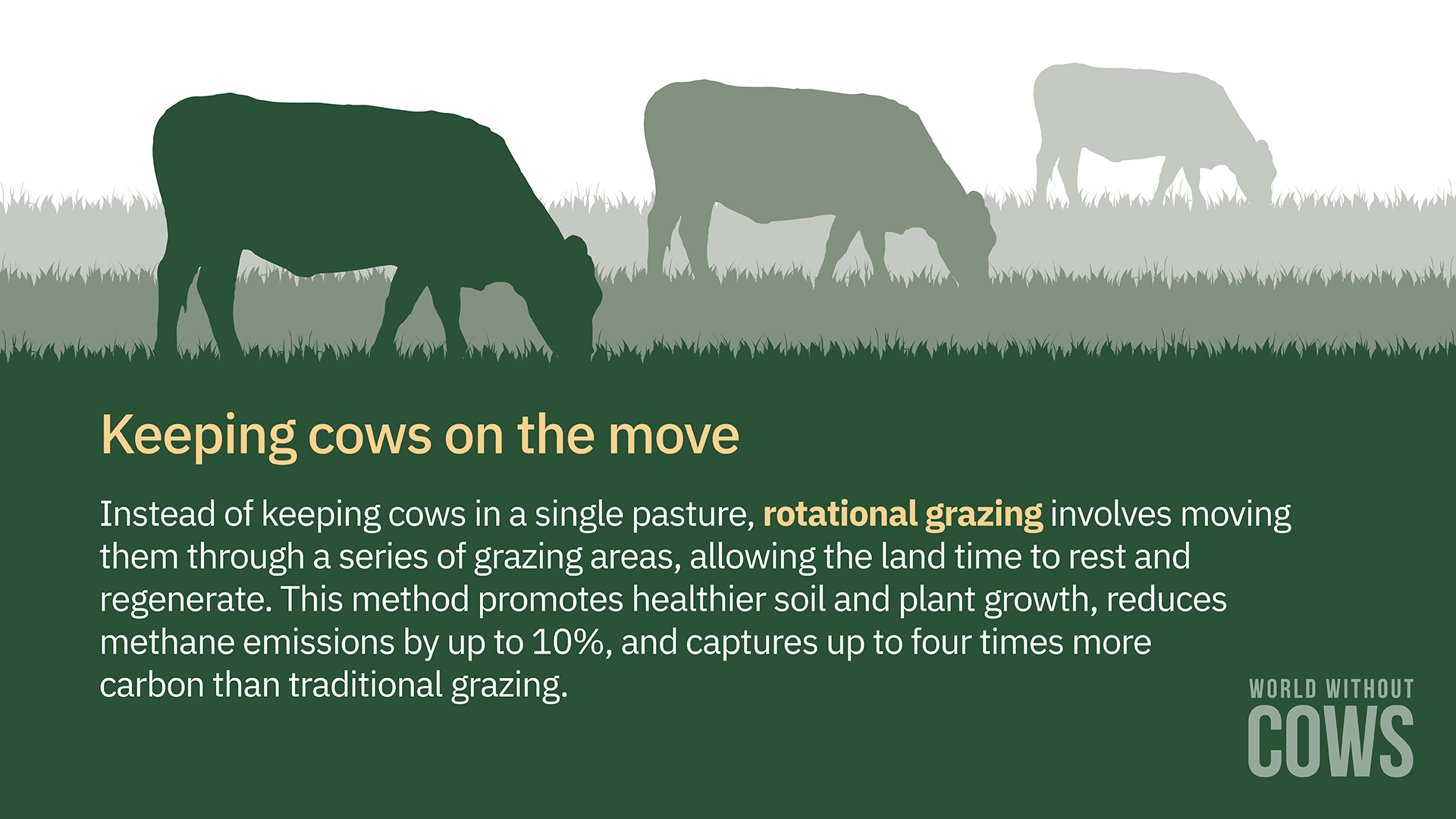

Known as rotational grazing, or adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) grazing, the method mimics how wild herds of bison once roamed the Great Plains in tightly packed groups — grazing intensively and moving frequently, allowing the previously grazed sections to rest and regenerate.

After Gabe’s production, Brown’s Ranch, shifted to rotational grazing, the first signs of improvement came quickly.

The soil turned darker. Water retention improved. Wildlife came back. His forage production doubled, then tripled. And, perhaps most surprising, he stopped relying on outside inputs such as fertilizers, feed and chemicals, because his land began to heal itself.

After more than two decades of implementing regenerative practices such as rotational grazing, no-till and cover cropping, the positive changes on Brown’s Ranch became even more clear:

Today, Gabe’s ranch is living proof that well-managed grazing cows are not a liability to the land. They’re a means to restore it.

He often emphasizes how the shift to regenerative practices like rotational grazing has accelerated change on his ranch and has shared in many interviews, “We have seen more positive change in the past three years than in the previous 25 years combined.”

While rotational grazing is now second nature for Gabe and many other farmers, it hasn’t caught on more widely — yet. What are the obstacles, and what might encourage farmers to move past them?

Despite a growing body of evidence supporting rotational grazing, Gabe says that many farmers simply haven’t had access to the information or training they need to put it into practice.

“The largest barrier is simply a lack of understanding,” Gabe notes. “Farmers and ranchers cannot implement what they do not understand. They are not often taught these strategies by land grant universities, extension, NRCS, or the myriad of other agencies and organizations who want to see them adopted.”

Even when agencies offer financial incentives to try new practices, the technical support often falls short.

“Far too often these agencies and organizations offer cost share incentives, but they do no good if they are not accompanied by education,” Gabe adds.

To close this gap, organizations like Understanding Ag and the Soil Health Academy are working to empower farmers through education on regenerative farming principles. Once these regenerative practices are in place, programs like Regenified offer outcomes-based verification and certification to ensure that the farmers’ efforts are recognized, measurable and aligned with long-term soil health and sustainability goals.

For farmers with limited financial or labor resources, the switch to regenerative practices can feel out of reach.

Installing fencing, setting up water systems and managing the movement of cattle do require time, planning and an initial financial commitment. However, according to Gabe, the costs are not nearly as prohibitive as many producers think.

“There is a misconception that making the change to adaptive grazing takes significant investment. This is usually not the case,” he says. “Most farmers and ranchers can begin implementing adaptive grazing strategies with little up-front cost. A good electric fencer, some portable posts and a few rolls of polywire is all it takes for most to get started.”

Practices like rotational grazing improve soil health, store carbon, filter water and boost biodiversity. But farmers can’t make the shift alone — they need reliable, long-term support. What’s missing in many countries is a unified national strategy that provides farmers with the incentives and support they need to produce more sustainably.

In the U.S., the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) offers funding and technical help for conservation practices like prescribed grazing, which manages the timing and intensity of livestock to improve land health. But access can be limited, and funding is often prioritized for more traditional approaches, making it harder for regenerative practices like rotational grazing to get consistent support.

Some countries have taken a bolder approach. In New Zealand, pasture-based livestock systems are supported by public investment in soil health and emissions reduction, including funding for research through the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC) and a government commitment of NZ $400 million over four years to scale up emissions-reducing practices on farms.

Similarly, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy now includes eco-schemes that reward rotational grazing and biodiversity.

Because of success stories like Gabe’s, rotational grazing is drawing global interest from farmers, scientists and policymakers who are interested in more adaptive approaches to land and resource management.

For farmers who do adopt rotational grazing, the change can be profound. Gabe has seen it firsthand.

“What we have found is that once farmers are educated and shown how easy it is to implement, they try it and quickly see positive, profitable results,” he says.

Turning potential into progress means making it easier to get started, not just with funding, but with better education initiatives, certification programs and long-term support that goes beyond the first grant.

Because with the right tools, knowledge and backing, the shift to rotational grazing isn’t just possible — it’s well within reach. And if we match interest with action, farmers won’t just keep up. They’ll lead.

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

At COP30, the world’s eyes are on Brazil, and the cattle ranchers leading a global transformation.

Restoring 40 million hectares of pasture could feed billions and ease pressure on the Amazon. Is the world paying attention?

New mini-doc explores deforestation, food security and the Brazilian cattle sector’s path to a more sustainable future

Mention Brazilian beef, and you’re likely to spark discussion about familiar themes: deforestation, emissions and blame. What do we find when we dig deeper? Here are the answers to five top questions about Brazil’s role in protecting the Amazon and feeding the world.

From science to the big screen: Discover how a single question grew into a global journey.

As climate change intensifies and the world’s population continues to grow, the pressure on our global food production system mounts. You can play an active role in shaping a more sustainable planet for future generations. Fill out the form below to learn more about how you can partner with us.

Receive notifications about the release date, new online content and how you can get involved