Cattle, greenhouse gases and the case for better methane metrics

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

There’s a widespread narrative that paints cattle ranching as an environmental villain, a major contributor to climate change. While it’s true that conventional cattle farming practices can have negative environmental impacts, emerging research suggests a more complex and nuanced story. What if cattle, managed strategically, could actually be part of the climate solution?

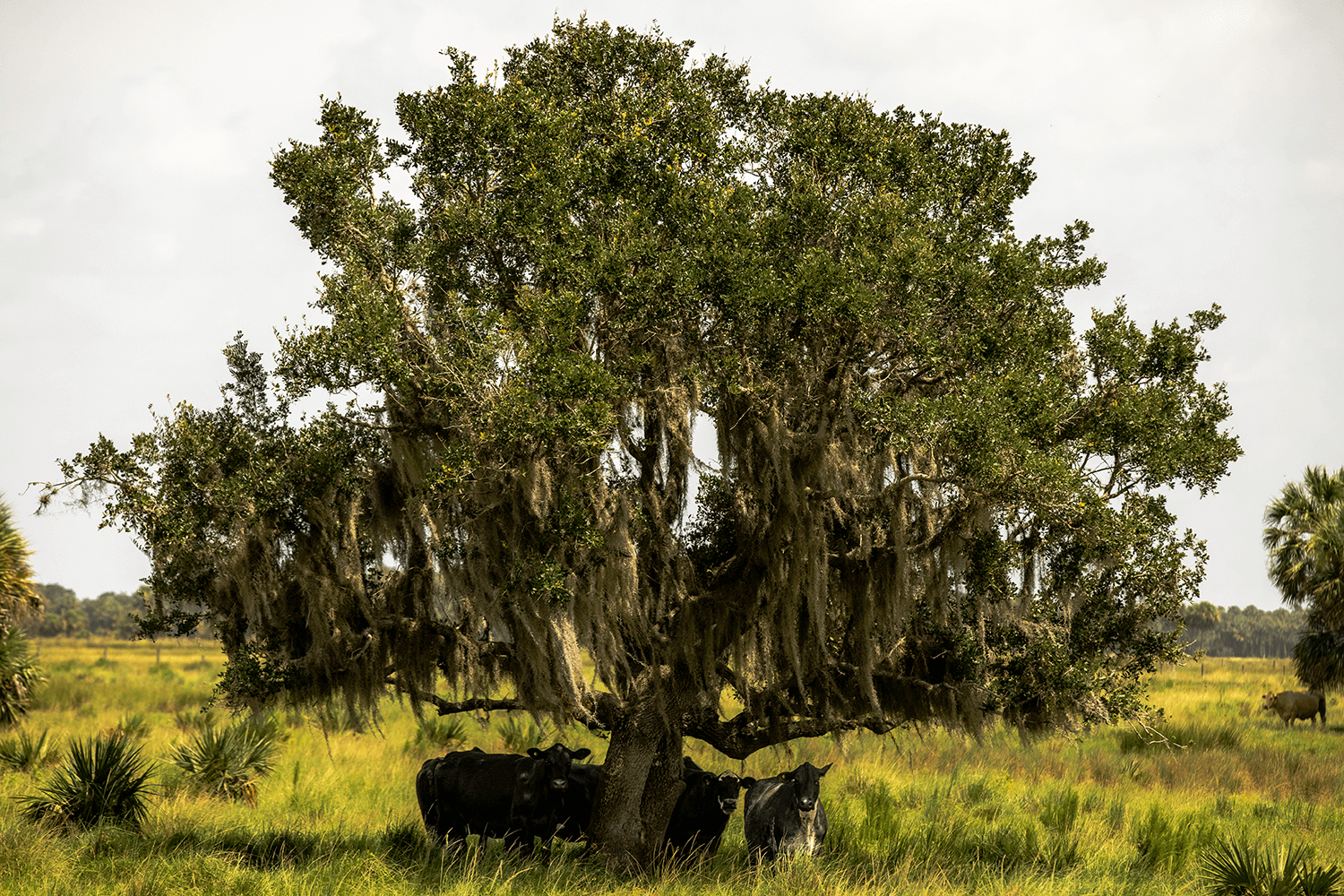

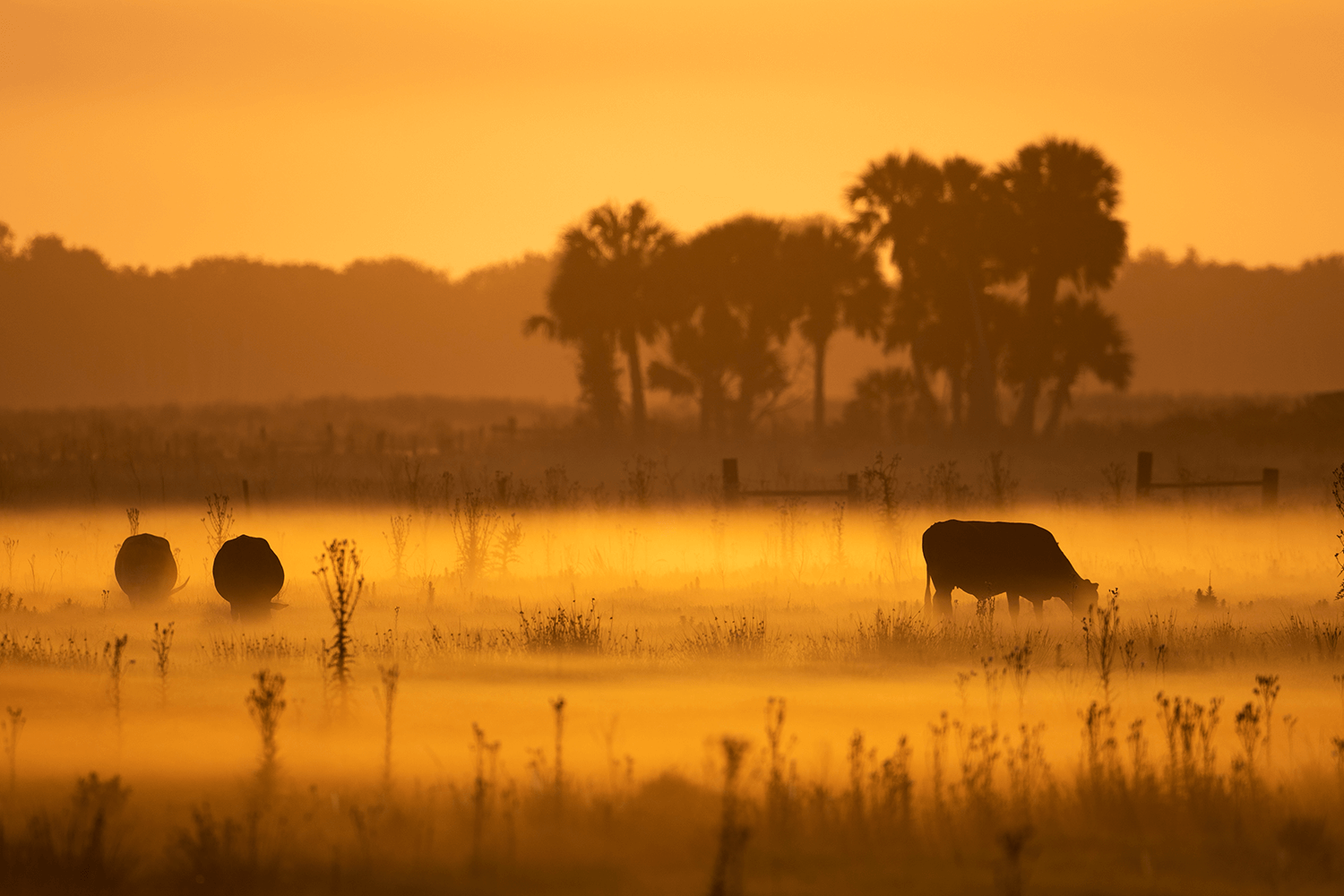

A groundbreaking research alliance at Archbold’s Buck Island Ranch in Lake Placid, Florida, is challenging conventional wisdom about cattle and climate change.

There’s a widespread narrative that paints cattle ranching as an environmental villain, a major contributor to climate change. While it’s true that conventional cattle farming practices can have negative environmental impacts, emerging research suggests a more complex and nuanced story. What if cattle, managed strategically, could actually be part of the climate solution?

A groundbreaking research alliance at Archbold’s Buck Island Ranch in Lake Placid, Florida, is challenging conventional wisdom about cattle and climate change.

A team of ecological and agricultural researchers has been investigating the carbon emissions and sequestration potential of the 10,500-acre ranch, which is home to more than 3,000 beef cattle. The alliance has developed a model for estimating the ranch’s carbon footprint — and the findings have been remarkable.

On average, Buck Island Ranch sequesters more carbon each year than it emits. It is a net-carbon sink!

The research has shown that carbon-negative beef production at Archbold’s Buck Island Ranch is not just a possibility — it’s a reality. And this same potential may extend to other beef ranching operations around the world.

“Every year, we sequester 1,201 tons of CO2 equivalent,” said Dr. Betsey Boughton, director of agroecology at Archbold. “And all of this work is scalable to other parts of the world.”

This information often surprises people who think of agriculture solely as a source of emissions.

“The narrative people have heard is that cows are bad for the environment,” she said. “So, we’re like, ‘Well, hang on, it’s not so simple.’ Grazing animals can actually change the function of grasslands. Cows are eating the grass and not allowing as much decomposition to happen on the ground. Without cows, we actually see more carbon emitted.”

“We’re trying to let people know that it is not just this black-and-white answer,” she added. “It is complicated, and we need to think about the whole story.”

While it is a complex issue, research has demonstrated that agriculture can be one of the most effective weapons in the battle against climate change.

The work performed by this strategic alliance has discovered a deeper understanding of the cattle-grazing carbon cycle, which extends beyond animal emissions to encompass the vital roles of photosynthesis, natural greenhouse gas emissions from the land itself, and importantly, the sequestration of carbon in the soil.

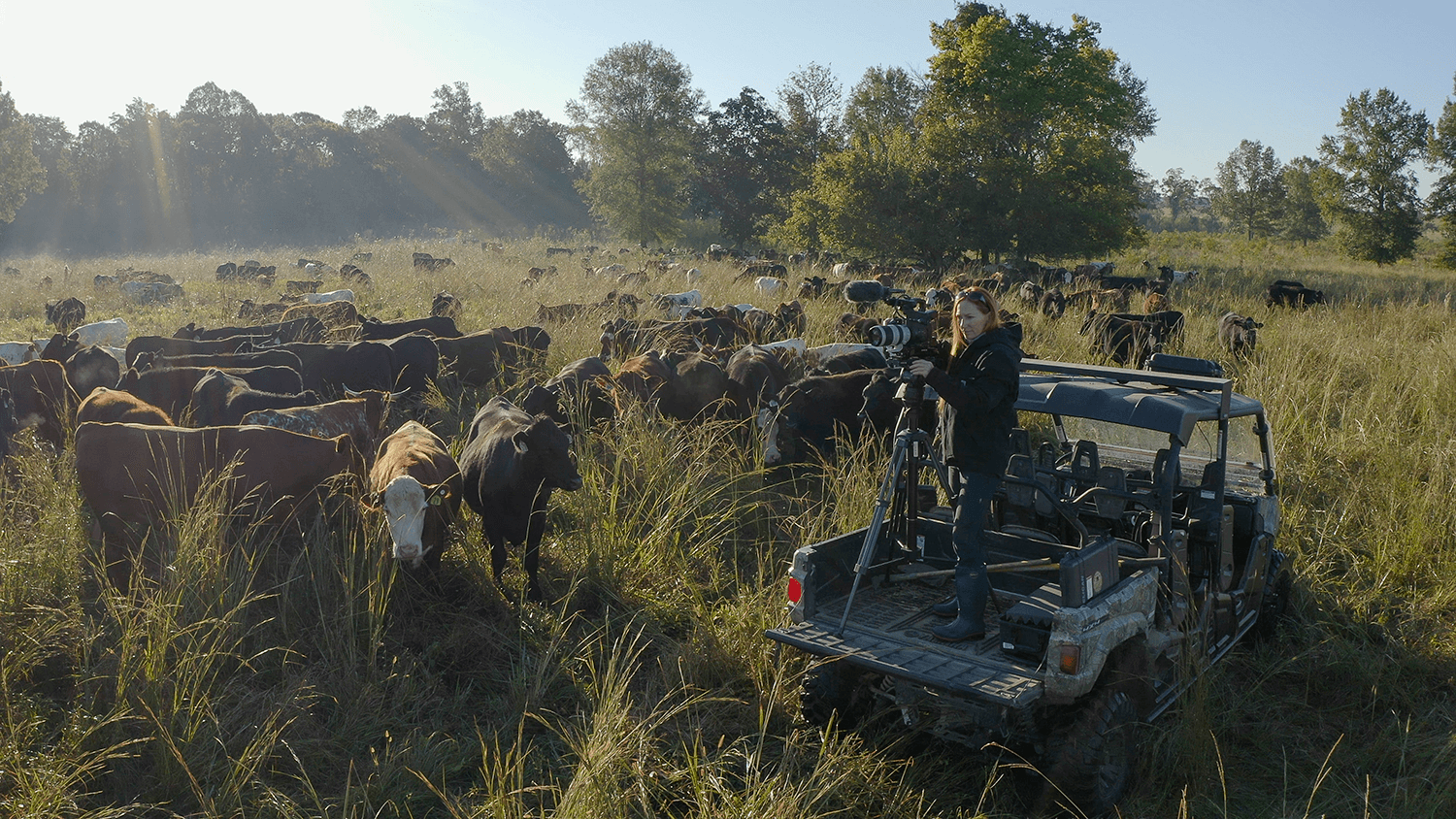

This six-part Planet of Plenty video series explores how grazing cattle affect the carbon cycle, the role of carbon sequestration in combating climate change, and other important findings revealed by the collaborative research alliance.

The research alliance explores the complex relationship between cattle and the environment, aiming to understand how cattle influence the ecosystem and how the ecosystem, in turn, affects cattle.

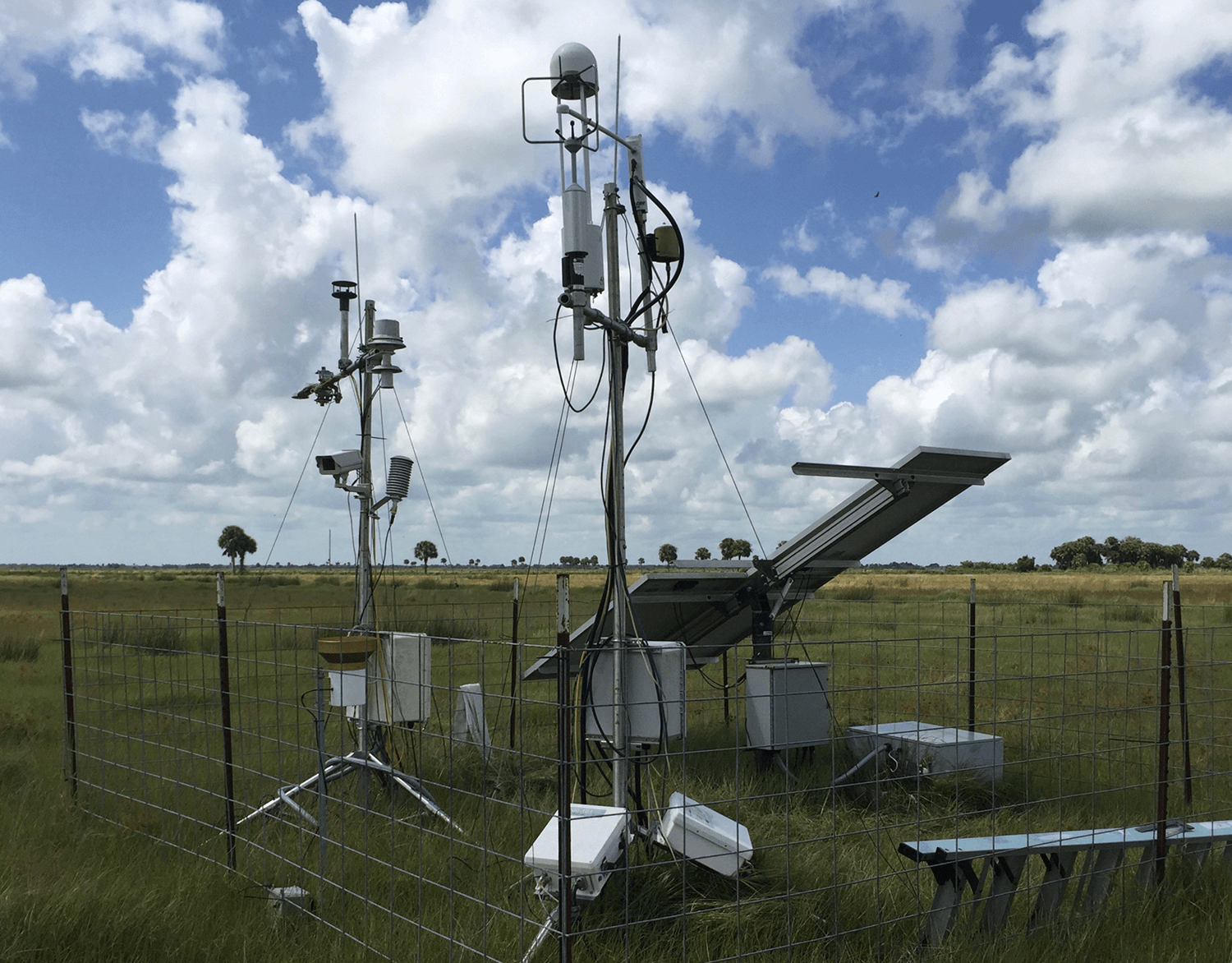

The team, led by Dr. Boughton, uses eddy covariance towers on the ranch to measure GHGs in the atmosphere and evaluate carbon capture by the soil. They also gather soil samples and track cattle-grazing patterns.

The alliance also used Archbold’s historical operations and economic data to model total ranch GHG emissions over several years, and they teamed up with additional partners to develop a GHG emissions model that includes carbon sequestration.

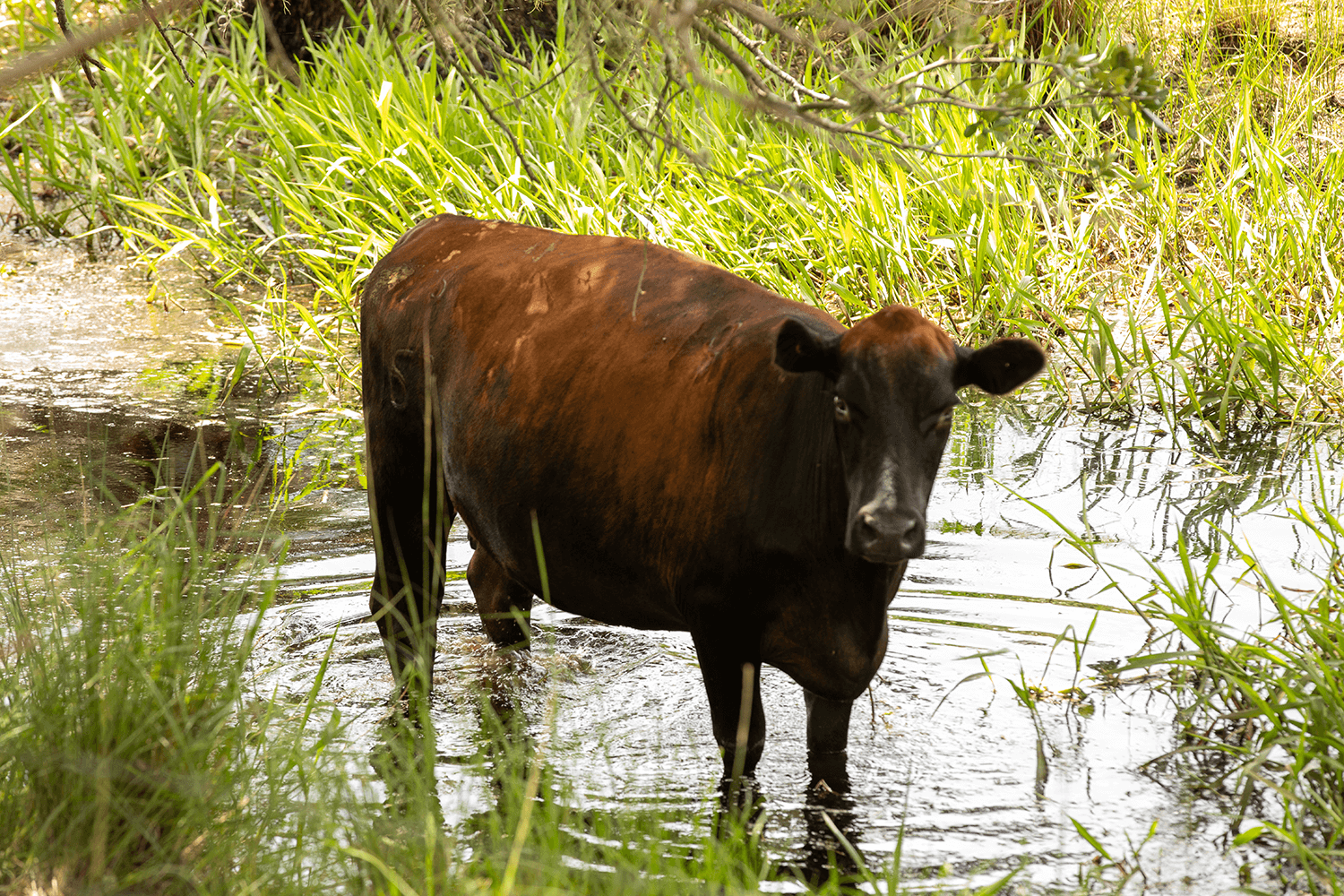

Because Buck Island is located within the headwaters of the Florida Everglades, the ranch contains a combination of semi-native pastures, improved pastures, wetlands and woodlands, Dr. Boughton says.

“Nineteen to 30% of the methane emissions from our pastures are from cattle, but the rest is from these wet soils and wetlands. So those are a really big source of methane that people don’t always acknowledge,” she said.

In Part 2, Dr. Vaughn Holder, global beef research director at Alltech, explains the connection between cattle and methane.

Cattle are ruminant animals that eat a variety of grasses, hays and fibrous plant materials that they swallow almost whole, chewing it only briefly. Ruminants have a unique, four-chambered digestive system that includes a large chamber in the front of their stomach called a rumen.

The rumen is like a giant fermentation vat full of billions of tiny microorganisms — bacteria, fungi and protozoa — that help break those plant materials down into simpler components that the cow can digest and absorb as nutrients.

This fermentation process creates methane as a byproduct. The microbes release methane during the breakdown of complex carbohydrates in the plants. Cows can’t use this gas, so they get rid of it by burping, a process known as enteric fermentation.

Agricultural researchers are exploring innovative methods to measure and mitigate methane production in cattle. Modifying diets, incorporating feed additives and encouraging the microbial population in the rumen to produce less methane are commonly viewed as effective and natural strategies for reducing methane emissions in ruminant animals. However, because methane plays an essential role in the digestive process, attempting to reduce it beyond a certain point can negatively impact the diet’s digestibility and the animal’s performance.

Understanding the difference between carbon behavior in fossil fuel production and agriculture is key to discussions about livestock’s impact on global warming.

Fossil fuel production involves a one-way release of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, unlike the cyclic process in agriculture, where carbon is absorbed and emitted within an ecosystem.

Focusing solely on carbon emissions from animals ignores both the CO2 absorbed by the ecosystem and the CO2 taken in by the animals. When cows consume plants, they digest the plants’ energy, emitting CO2 and methane in the process. Methane from livestock breaks down in 10 to 12 years, returning as CO2 without adding net carbon to the atmosphere

Put simply, CO2 is a stock gas with no natural removal cycle and a long lifespan. Stock gases accumulate over time because they stay in the environment. In contrast, methane is a flow gas with a natural removal cycle through chemical reactions that occur in the atmosphere — and it can be absorbed by soil and vegetation.

Learn more about the differences between carbon dioxide and methane.

“Cows are a very important part of our food security picture,” Dr. Holder explains in Part 4. “Cows have the unique ability to take things that we can’t eat and turn them into things that we can eat. This is a concept that we call upcycling, where they make more human-edible protein than they actually consume.”

Cows convert non-edible resources into nutritious food, such as high-quality milk and meat. Research has shown that as much as 86% of the feed materials eaten by cattle are inedible by humans. Cattle also efficiently utilize byproducts that would otherwise create disposal challenges. Composting these byproducts would increase their carbon footprint fivefold — and sending them to landfills would raise it by 50 times, Dr. Holder says.

Cattle grazing has a notable impact on the carbon cycle by promoting root growth, decreasing decomposition, and altering plant composition. Studies show that pastures with grazing cattle can have a net cooling effect on the environment due to enhanced carbon capture and reduced emissions.

“When you pull those cattle off of that pasture, the methane production drops slightly because you’ve taken the cows’ methane out of the story,” Dr. Holder explains. “But then, without cows, that sequestration by the environment goes away significantly. You actually end up with a pasture that is net emitting with no cattle on it. So now not only do you not have any food being produced off of that pasture, but that pasture is now emitting more carbon, more greenhouse gas equivalents than it was in the winter when there were cattle on it.”

Removing cattle from pastures reduces carbon sequestration and increases emissions, underscoring the critical role of grazing in plant growth and carbon cycling. Grazing practices influence both carbon uptake by plants and its retention in the soil, highlighting cattle’s role in carbon sequestration.

“We have to think about this as a holistic system,” Dr. Holder says.

Carbon sequestration involves moving CO2 into the soil and balancing its inputs and outputs. Plant root growth and soil microbial activity are essential for converting captured carbon into a more stable form. Studying the soil microbiome is key to understanding and enhancing carbon sequestration.

“I do think there’s an interesting win-win situation here for ranchers in carbon sequestration because typically the practices that improve carbon sequestration also improve forage production,” Dr. Boughton explains in Part 6. “So things like irrigation or rotational grazing, legume integration, all of those things increase productivity.”

Properly managed grazing systems can enhance carbon sequestration, whereas overgrazing can hinder it. Future research will use models developed at Buck Island Ranch to explore carbon sequestration on a global scale.

Why the global warming potential of methane emissions from cattle production needs a closer look

At COP30, the world’s eyes are on Brazil, and the cattle ranchers leading a global transformation.

Restoring 40 million hectares of pasture could feed billions and ease pressure on the Amazon. Is the world paying attention?

New mini-doc explores deforestation, food security and the Brazilian cattle sector’s path to a more sustainable future

Mention Brazilian beef, and you’re likely to spark discussion about familiar themes: deforestation, emissions and blame. What do we find when we dig deeper? Here are the answers to five top questions about Brazil’s role in protecting the Amazon and feeding the world.

From science to the big screen: Discover how a single question grew into a global journey.

As climate change intensifies and the world’s population continues to grow, the pressure on our global food production system mounts. You can play an active role in shaping a more sustainable planet for future generations. Fill out the form below to learn more about how you can partner with us.

Receive notifications about the release date, new online content and how you can get involved